Black Art: A Brockman Gallery Legacy

Season 15 Episode 4 | 56m 38sVideo has Closed Captions

Brockman Gallery was the center of a community of Black artists in L.A. from 1967-1990.

The Brockman Gallery in Leimert Park was the center of a community of Black artists from 1967-1990. Founded during the heyday of the Black Arts movement and two years after the Watts uprising, it would go on to feature artists that included Betye Saar, Noah Purifoy and John Outterbridge. The Brockman Gallery ushered in a new era of Black artists, helping them penetrate the mainstream art world.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Artbound is a local public television program presented by PBS SoCal

Black Art: A Brockman Gallery Legacy

Season 15 Episode 4 | 56m 38sVideo has Closed Captions

The Brockman Gallery in Leimert Park was the center of a community of Black artists from 1967-1990. Founded during the heyday of the Black Arts movement and two years after the Watts uprising, it would go on to feature artists that included Betye Saar, Noah Purifoy and John Outterbridge. The Brockman Gallery ushered in a new era of Black artists, helping them penetrate the mainstream art world.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Artbound

Artbound is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipMan: In the late sixties, there were so few venues that were available to any artists of color.

Woman: So many people, African Americans, especially, moving to L.A. with the hope of creating a new life 'cause they thought this is the land of opportunity.

Man 2: If you look at the history of L.A., African- American artists was gradually excluded.

Woman 2: We were hungry to learn about Black history.

Woman 3: Most Black artists were being told, "You can't make a living as an artist."

Woman 4: We need to build our own table, rather than trying to fight our way to getting a seat at someone else's.

[Music playing] Announcer: This program was made possible in part by a grant from Anne Ray Foundation, a Margaret A. Cargill Philanthropy; the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors through the Department of Arts & Culture; the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs; and the National Endowment for the Arts.

[Creaking] [Music playing] Charles Dickson: My beginnings in the creative field was when I was five.

I was carving wood at the age of five.

I discovered that I liked to carve bricks.

When I got into junior high, I had a chance to be in the woodshop and also the art department.

There was an art department which I could express my creative self.

I started to sell my work.

It gave me the possibilities to enjoy this lifestyle.

Man: That's the most important thing, is elevating our black and brown L.A. artists, particularly the ones like you.

You've been doing it forever, but the world is gonna see this in a way which they've never seen it before.

Mark Steven Greenfield: This is my contemporary icon to Francois Mackandal, and I'm gold-leafing the halo that's around his head right now.

Voice-over: I really was interested in chemistry, and I had a little explosion in my room and almost gutted it, and my mother gave me a whipping that lasted for the better part of 3 weeks.

And so, as peace offerings, I started giving her little drawings that I would do.

She showed them to her friends, and then, after a while, they said, "Oh, he might have some talent," so she decided that it was OK to cultivate that.

If you know the traditional use of an icon, oftentimes it was carried into battle.

It was a way of telling people that God is on our side.

We have a whole new group of battles that we need to fight.

We need a whole new set of icons.

And so what I'm doing is taking lesser-known characters out of the African diaspora, venerating them by this process.

Woman: I have just recently opened up a scrapbook that my mother kept from the day I was born, I guess, from scribblings to actual drawings.

I had beauty around me all the time, even as a baby.

From my bedroom window, I could see San Bruno Mountain, and I would be fascinated by the way the grass would just blow in--in the wind.

I like to look at my paintings now just to see what I've done, because every painting is different, even the way I'm working with acrylic now.

Voice-over: There are never any two times that are the same, so it's fascinating to me sometimes to go, and some of the paintings where the gallery sells them, they go to collectors, then I don't see them again.

Man: This is an older piece.

It's 1972.

It was probably one of the last adventures that I had with LSD.

You didn't grow up in the sixties when--if you'd-- weren't actually taking LSD, you weren't hip.

So... that gets into a whole 'nother line of cultural exploration, but anyway... Voice-over: You say my interest in art, where does it begin?

Well, I think as a young child, my father was doodling one Sunday afternoon just on a piece of paper, and I was fascinated with his scribbling.

So I started trying to do it myself, and eventually, that grew into trying to learn how to draw.

Man: My name is Alonzo Davis.

I'm an artist, originally from Tuskegee, Alabama, migrated to California, 1956, with my brother, Dale Davis.

Man: I really feel like I was an artist first, and so that was always there.

As a kid, I was a builder.

I'd make things from whatever I found, and being an adventurous kid and with a good imagination.

Alonzo Davis: Went to high school and college in Los Angeles.

Art history was about that much African and the rest was European.

[Static buzzes] News anchor: Gutted shells of buildings, flames raging out of control, and an atmosphere of apprehension still hover over the quieting Watts section of Los Angeles.

Here for successive days and nights, mostly in the nights, the long, hot summer had erupted into violence.

Woman: The August of '65, across the country, there's a lot of things happening civil rights- related, right?

You had Civil Rights Movement, you had the Voting Rights Act.

You had so many different political movements going on, so much interest in or so much conviction around trying to get equality for African Americans.

Dickson: I remember coming from high school that evening before the riots, where I saw them breaking up the sidewalk so that they can make rocks and stones to throw at anything that came down there at night.

And I was wondering, "Wow, what's going on?"

So, later on that night is when everything kind of broke up.

I had never been in any kind of thing like that before.

Greenfield: I remember the whole neighborhood more or less being invaded by the National Guard, and seeing jeeps with machine guns on them on the street corner was a little unnerving.

Dale Davis: The Watts riots was a reminder, hard-core reminder, even though I thought I was special and separate from it because I lived in a more middle-class neighborhood at that time, there was no difference.

You were just another African-American person, Black person in the neighborhood and subject to whatever was going on.

Jenkins: That was in my freshman year, and when I came home, all hell was breaking loose.

I just remember all of those state police, with weapons being pointed at us.

We just thought, "Wow, man," uh, 'cause the fact that the riot--when it came west and it got as far as Crenshaw, that put a whole 'nother kind of definition in the city; in particular, white flight.

Alonzo Davis: At the same time, the L.A. County Art Museum was moving out of the "community" to, uh, a more affluent neighborhood, and many of the artists were not included.

Dale Davis: And so Alonzo and I, my brother, we decided that we would go on this grand tour and because, at this point, we're adult enough to really kind of have a understanding of what had happened to us and, really, to the world.

Alonzo Davis: So, in '66, we said, "Let's take a trip and see the Black artists in the United States."

And along the way, we had discussions about, "Wouldn't it be great if we open a gallery?"

[Music playing] One would drive, and the other would sleep in the back of the Volkswagen.

Ha!

That's basically the rules, and we tried to, uh, uh, stop at safe places 'cause we knew the South had, uh, some--some different standards.

We visited a number of HBCU-- Historically Black Colleges-- from Texas to Jackson, Mississippi to Jackson State, and then from there to Durham, North Carolina, where my dad was teaching psychology, and then got to meet Romare Bearden in New York City, who was probably the most impactful because of how generous he was with information.

Dale Davis: My mother Agnes, the Aunt Louise, they were like, "No, you know, you need to go to business school.

You don't know what you're doing here."

Alonzo Davis, chuckling: "You have--you have no business trying to open an art gallery.

Where is this place, anyway?"

Dale Davis: People who don't know anything about land covenants, that's a piece of history that you need to check out.

There were actual laws on the books that were--that said, if you were anything other than the dominant group, you couldn't buy a house there.

Alonzo Davis: My mother saw the determination and said, "Go next door and see Mr.

Parks.

He's a lawyer."

Dale Davis: So he was critical in helping us understand that we were there, we were safe.

We had mentors.

Ben Caldwell--prime person, reconnected with coming back--who helped to convince us that we could do this thing.

And so we had the discussion and we won, which was to say, "No, we're not going back to school.

We've already been to school.

We have degrees.

We think we know what we're doing, and we're gonna open up this gallery in Leimert Park," which was called Brockman Gallery.

Alonzo Davis: We signed that lease in January and opened this space that spring.

[Jazz music playing] Keith: When Dale and Alonzo opened the gallery in 1967 in Leimert Park, it seemed like it was a perfect location to open up a gallery space.

You had Baldwin Hills, you have View Park, you have a, you know, huge group of African Americans in South L.A., South Central Los Angeles.

Dale Davis: And then, at this point, we'd met all these very interesting and dynamic artists through Will Rogers...Park and that gymnasium, which is where-- that was the only place that we could show, in a gymnasium or a church basement.

Dickson: Will Rogers Park is a pivotal point of Black art in L.A. because that's where Noah, David Hammons, John Outterbridge--I could go on and on about the people that were involved at that time.

It was just a grassroot movement of Black art.

Out of that, I met Dale Davis, I met Alonzo Davis.

Jenkins: The first time I met those guys, I think it might have been at an exhibition.

My work was the exhibition on the street.

Eventually, I was contacted--might have been Alonzo--to become a member of the first artists to paint the murals on, uh, Crenshaw.

But at the same time that I was doing that project, I was also painting with Judy Baca in the valley in her Tujunga Wash mural.

We'd start painting in the valley at about 8:00 in the morning, finished by noon because it'd be so hot over there.

I'd leave the valley and then I'd come back over to Crenshaw, and I would be painting on that wall.

Greenfield: I was introduced to Brockman by John Riddle.

He introduced me to Alonzo and Dale.

Had to be 1969, something like that.

Most white artists, they--they had a number of places where they could put--get together.

I'm thinking Gorky's downtown, but we really didn't have that kind of--of community at the time, so Brockman actually provided us with that place where we could all come together and discuss things.

Tami Outterbridge: It was a vibrant space where we could say what we wanted to say, be who we are, challenge the system.

And it provided us with the coming together, the communal place and space to do that, not just in Leimert Park, but I think it was also a beacon, a homing place for the Black Arts Movement as well.

Even as a child, I felt the power of what was happening at Brockman Gallery and the artists who were a part of it.

Jackson: Each artist who showed at the gallery invited their friends, and their friends invited friends, and then, between Brockman Gallery and Gallery 32, the word of mouth, and then the start of the Black Arts Council, then people started coming to both galleries, so we'd have--one gallery would have an opening on Friday, the other on Saturday.

People would go back and forth to see, "What are we gonna see at this one?

What are we gonna see at the next?"

And also, people in the community learned the idea that you could have artwork, real artwork, inexpensively from young artists.

Dickson: Brockman was, like I say, very politically aware in the process of unifying artists and letting us know that we did have a voice, we could have a voice within those things.

Alonzo Davis: I think art challenges and, um... militant images provoke.

Some people only like flowers, so we didn't always give the sweetest side, uh, to life, uh, in the--in the community, which makes me think of Noah Purifoy's installation where he re-created all of the upstairs of the gallery loft into, uh, a southern living scene with smells and newspaper and motorized mannequins and a bed under sheets.

And a number of people--heh!--did not want to accept, uh, the hot hair comb and the--the smell of grease or bacon or any of those things that, uh, are associated with difficult living standards.

[Chuckles] I'm laughing at the way I said that.

Heh heh!

But reading between the lines is the best way sometimes.

Ha ha!

Dale Davis: This is not a criticism, but our people tended to want to credit us for sponsoring African-American artists only.

That was not the case.

The case was we were sponsoring everybody.

Those--all the artists that never had a chance.

Alonzo Davis: Number of, uh, artists from the Japanese community, Hispanic, Latino, primarily, uh, Mexican-American community also participated in.

Keith: I think what made what they showed interesting is that they were willing to take risks on artists that maybe weren't commercially, um, popular.

I think what I loved is that they said, "You know what?

This artist is really interesting"-- a David Hammons or a John Outterbridge or a Noah Purifoy or a Betye Saar--and saying, "You know what?

I want to give this artist a chance" and allowing them to show their work in that space.

I think that's what also made it equally as interesting.

Betye Saar: Which is this one, 1962.

There were no galleries that carried Black artists' work.

Not--not a woman artist of color was in a gallery.

We had no galleries.

Our places where we exhibited were, um, like at a library gallery or a church gallery or somebody's home.

They would have a tea and they would have your work exhibited.

Alison Saar: Even when I was in New York, that there was, you know, a lot--a huge discrepancy in terms of the inequities of women artists being shown compared to white male artists being shown, the representation of women artists and women artists in the museums, which is why the Guerrilla Girls was around and really pushing.

Betye Saar: The places that we were--we could show our work were very limited, especially in the sixties and through the seventies.

There were no galleries, really, until the Brockman brothers started their gallery.

Dale Davis: You're trying to make it happen and you're--you know, so we knew about commitment and you do what it takes, and it was that kind of attitude that we still have that gives us a link to success that is honorable.

Alonzo Davis: My brother was good at numbers and keeping books, and I was good at identifying the artists and... uh, that coordination and communication.

And so we did it and learned by the seat of our pants.

So I tell people often that, uh, there's a lot of ways to learn, and one is by experience, the other might be in school, and, uh, trial and error.

If you don't risk failure, you don't...uh... realize successes.

[Birds chirping] Woman: When I built the house, you see, it's pretty white, but I didn't want it to be that way.

The kids and I did the mural on that side, but we really wanted something more impactful on this wall, so that's when I had Keith Williams come down.

I... just said, "Look, I like your graphic sense, and... here's a wall.

Do you"--ha ha!-- "and just do it."

And he was the one that then had these playful, um, children and things.

Alonzo Davis was my art teacher at Crenshaw High School, so that probably was in '69; not my first year, my--probably my second year, '69.

And I was excited to take art at the time 'cause I was a pretty academic student, and I--but I had this fantasy of wanting to draw and things like that.

So I took the class, and I had, um, I did this assemblage, I don't know.

Uh, yes, it was assemblage back in the day.

Anyway, um, so I turned in this project, and I thought I--it was pretty fantastic-- to me--but, um--ha!--Alonzo looked at the piece and said, "You know, Simmons, you have a great eye, but maybe you should be a collector," and I was like...

I met Kenturah Davis when she was working at Gemini GPL.

In our interactions, I wanted her to do a piece, and so I commissioned her to do this piece of my mother when my mother was 17.

And so she said, "Well, what's your mother's favorite, you know, saying or whatever?"

And I said, "Well, you know, the Lord's Prayer," and so Kenturah wrote the Lord's Prayer 50 million times to make this image.

So you can see.

If you get close, you can read the Lord's Prayer that--she used just a regular graphite pencil to create this image.

Kenturah Davis: My relationship with Dr. Simmons is so deep 'cause she has a strong connection with so many artists, but she engages with you at a level that feels so personal and intentional.

And she really saved me--heh!-- at a time where I was really trying to figure out, like, "Can I proceed?"

and "Can I, uh, make a career of this?"

And that period of time still means so much, because it was kind of a pivotal moment where I stepped out to really invest in myself and give the time that the work I wanted to make needed.

My first gallery was in Leimert Park, on the same block where the Brockman Gallery was.

Dale and Alonzo would come, and Dale in particular really made an effort to connect and express his encouragement around what I'm doing, having that ongoing kind of rapport of this artist that I look up to and who made a big impact here.

It was kind of a legacy of the Brockman Gallery.

It was an aura, 'cause my dad's an artist.

He came to L.A. in his late teens, and so he was sort of trying to figure out his way, and he developed a friendship, mentorship with John Outterbridge, him imparting that fact and talking about artists like him and artists of that generation.

It sort of was this layer of understanding around, um, the sort of impact of Black artists in the city of L.A. Alonzo Davis: We connected not just on the business side, but also on the family side.

Tami Outterbridge was the daughter of John Outterbridge, who was one of the first artists we exhibited.

Woman: So...this is a lot of materials in regards to your father from the Brockman Gallery.

Tami Outterbridge: Wow.

[Sniffles] Yeah--oh.

[Sniffles] I saw little Tami right away.

[Sighs] Wow.

[Sighs] [Sniffles] This is just a freehand poem.

I would have been two years old.

I have never seen this before.

So this is...so beautiful to be able to follow and track in his footsteps.

Voice-over: Watching him leave sweat, blood, tears with institutions like Communicative Arts Academy he co-founded; Watts Towers Arts Center, where he was a transformational director there from 1975 to 1992.

Rosie Lee Hooks, the director now, says, "Had John not been here to lay that foundation, we would not be able to pursue the excellence that we're pursuing now."

World-class arts programs that he instituted while he was director there.

He's sharing so much in these handwritten notes about his process...his thoughts, what goes behind some of the works that were shown at Brockman.

This is so much of his life that was shared with Brockman Gallery and Alonzo and Dale, so this is amazing.

Assemblage probably felt very natural to my father.

Coming to Los Angeles and connecting with this community of people who were thinking and working in ways that we call assemblage probably felt like home to him because in Greenville, North Carolina, my dad says that the first gallery, the first museum he ever saw was his father's backyard.

Alonzo Davis: If you look at the history of L.A., uh, you realize that, uh, African-American artists was... gradually excluded.

The Watts riots took place, "Signs of Neon."

Noah Purifoy and other artists gathered debris from the riots to create artwork as a result of that kind of cultural explosion.

Alison Saar: As David Hammons called it, "Rousing the Rubble."

They started picking up all those charred bits, pieces of melted stuff and started putting these things together, and it was kind of looking at a space that had been destroyed, but these kind of phoenix works that were rising up from the ashes.

And I think Black artists is that, you know, we don't necessarily have the money to be buying $500 rolls of paper or spending $50 on a canvas.

A lot of recycling happens.

A lot of just, uh, you know, gathering what's kicking around sort of becomes part of it.

And I think there's also, for myself, in using used and found materials, is that, you know, I kind of feel like there's a spirit.

But I think that they really understood that those materials, you know, came through the fire, you know, survived through the fire and was rising up through these ashes, and so it was powerful material.

The most important piece that my mother made that's most widely recognized is "Liberation of Aunt Jemima," where she was taking on derogatory Black images and turning them on their heads and empowering them.

Alonzo Davis: My mother and my aunt were the opposition and the greatest supporters.

While they were reluctant for us to do this, they became our biggest supporters and--and friends and really helped us with their support, make this venture work.

Dale Davis: If you have a business, you always need support staff.

Too often, you can't afford, if it's a new business.

What you can afford-- heh heh!--are volunteers, so that--you know, they were initially the volunteers.

They volunteered throughout the entire history of the gallery, and over time, you know, they brought their team of professionals with them, so they were--it was a cadre of city librarians and county librarians.

They became a part of the Brockman family.

Keith: Brockman Gallery established, one, is that there is an active collector base here in L.A. that wants to support African-American artists.

I think you had a whole, you know, group of Black doctors, for example, that would regularly go to the gallery, would regularly buy work from the gallery, and so I think that it just kind of awakened in people this idea that, "Oh, wow, there are not just Black artists, but there are also Black collectors who want to support this work."

Alonzo Davis: But we did find support in the greater artist community.

We were members of the L.A., uh, Arts--Art Gallery Association.

Gradually, um, the entertainment and the Hollywood, uh, community, uh, trickled down into the gallery, and we were fortunate to have people like Sidney Poitier and visitors to that facility.

And as they came, others came, sort of--sort of opened the door to new kinds of clients and sort of let the neighborhood know that we had reached a level of acknowledgment.

Dale Davis: Well, those were your liberals, and they knew about us because they were liberal people, and so they-- they came to us to see, out of curiosity, "Well, what are you doing?"

or "We'd heard about 'em," like Ben Horowitz.

He was early promoter of Charles White.

How did you miss that, and how did you miss the opportunity to go to his space and stand up in Heritage Gallery and try to shine and convince him to do whatever it is you've had in your mind, that you had plans for him, even?

Same thing with Joan Ankrum.

Oh, my God.

"Sweetheart, sweetheart, just-- you need to come over."

You know, these were the people that you didn't know the power they had because you were--you were too close to the picture.

You were too close to the example of what it's like to go beyond your community.

Alonzo Davis: Joan Ankrum exhibited Bernie Casey, an actor, football player, poet.

Ankrum also exhibited, uh, Suzanne Jackson, who is a former gallery owner.

She had Gallery 32 and is currently exhibiting in the Whitney Biennial in New York right now.

Jackson: When I came--moved back to Los Angeles and took the big 5,000-square-foot loft space, they knew I was really serious 'cause I came back with my little baby as well, by myself.

I was serious about being a painter, and they helped me the first, you know, year or so that I was there with paying the rent, which was really low for that big a space.

Mrs. Ankrum, of course, kept all the records.

She--if you go into her file at the Smithsonian, every event on African-American artists that happened in the city, she had all the brochures, all the announcements.

When we were doing the Sapphire Show, I was just showing all the women, of all kinds.

I showed Betye Saar, my favorites: Barbara Chase-Riboud, Rosa Bonheur.

I showed all colors of women.

To me, that related, as women.

Alison Saar: I just really loved that community.

My mother was very close with Suzanne Jackson, and Suzanne Jackson also was-- had a little space that she was showing at.

Jackson: Betye also had children.

She had 3 daughters.

They were little babies then, which are kind of--you know, I remember they were little girls.

That whole family has kind of a legacy that Betye has built, has a great deal of respect as examples of women artists in that one family, combining everything that they know, skills and themselves as women.

Alison Saar: I feel really fortunate that coming into the art world in the eighties, that a lot of doors had been opened for me beforehand, and all these women artists that really, you know, put their foot in the door and kept it open for the next generation, and so I try to, you know, recognize whose shoulders I'm standing on.

Women artists really kind of paved the way for us, and, hopefully, you know, some folks will use my shoulders.

Jackson: When Gallery 32 closed, most of the artists went over to Brockman.

Dale Davis: You know, right place, right time, right attitude, willingness to work, willingness to share the profits.

We went through a period where we'd have a show and it wouldn't sell anything, and artists would kind of look at you like, "What did I just go through to provide you with my life, and for naught?"

So Alonzo and I decided, "You know what?

We got to be stronger than that," and so, hence, the Brockman Gallery Production.

Greenfield: The thing that--that always struck me was that I knew it had to be difficult for an artist to actually run a gallery, because inevitably, there would be some sort of conflict of interest that would come into play, 'cause running a gallery is no joke.

Heh!

Alonzo Davis: We had run into the crossroads of the demand by those like Cecil that you mentioned, that we become more community-engaged.

Uh, we had an interest in community, but it was not always financially feasible.

So, at one point, I went to see Maxine Waters, a congresswoman, and, uh, she said, "If you open a nonprofit, I can point you in a direction of where you might find support."

Jenkins: This is the reason, on a certain level, entry into my exiting mural painting, because the problem became the money and the fact that there was government grants that people were writing for to get the money to do the paintings.

Dale Davis: Well, we got a big grant, CETA, which stands for Comprehensive Employment Training Act, and it was a government program with a lot of money.

Jackson: The Brockman Gallery Productions' CETA program was the only one where the artists were hired to make art.

We were actually making our own programs based around the fact that we worked in our studios.

We made public art in public places, and we set up workshops or open studio spaces so people could come and see how an artist works.

We had panels and, you know, and basically, it was a public art program, so the fact that some of us were working on murals, wall--we call them walls, actually, not murals, but walls in the community where people could see us working.

Greenfield: We had not just African-American artists.

I mean, you had Ricardo Duardo that was doing work there, you had Hiroshima.

Uh, Hiroshima got its start at one of the music festivals that Brockman put together.

Brockman collaborated with John Outterbridge to start the Watts Music Festivals, jazz festivals, which I was able to take over later on, and I think now they're probably close to 45, 50 years old.

Dale Davis: One of the things that was surprising about the CETA program was that you had to spend the money before you got the replacement money, so it was--it was very tricky, so now we had become fund-raisers, so we did a lot of fund-raising.

We had fish fries, we did, you know, special programs, but it gave us an opportunity to open up more of the studios along that corridor to the point where we had all of the storefronts except for one.

So now, we have an opportunity to sublet all these other spaces, and we built a reputation and a cadre of artists who needed places to work.

Greenfield: The time of the CETA program was when I actually joined Brockman Gallery Productions, and I was the visual arts and graphics coordinator.

But during the CETA program, one of the things, one of the outgrowths of that was a mural program.

It gave us an opportunity to kind of hone our skills when it came to mural painting.

As an outgrowth of that was the Street Graphics Committee, which--Joseph Sims was the chair of that.

It lends itself to the whole idea of what happened with the Crenshaw Wall.

Alonzo called everybody up and said, "We're gonna go and paint the graffiti out on this mural on Crenshaw and 50th."

And it was, like, a 500-yard wall of nothing but just graffiti.

Crips and Bloods, the whole thing.

It seemed like L.A.P.D.

rolled up on us around 1:00, and they said--they cited us for defacing public property.

Robert Farrell, who's a city councilperson, he was able to get all the charges dropped and got us small stipends for actually working on it.

Alonzo Davis: CETA program, it also gave us the opportunity to, uh, get support, um... to--to the Olympics in 1984.

[Static buzzes] Jim McKay: This is the day that Olympic traffic officials had been dreading, that day when competition will be going on at 3 venues in the same area: track and field at the Coliseum, in the middle of your screen; boxing in the sports arena to the right; swimming to the left nearby.

In all, some 200,000 people will pass through that area today to be... Alonzo Davis: 1983, we secured support from the Olympic Arts Committee after being rejected maybe a couple of times.

And, uh, someone spoke to the head of the Olympic Arts Festival about why there were no murals, and they...said they wouldn't come forward financially unless there were murals.

So, out of the trash heap came my proposal.

Man: My goal in Los Angeles was to try to create a festival that had its own validity, that was a celebration of all of the arts, that sort of rejoice the eye and the ear with new things, uh, to see and hear.

Given the amount of avant-garde work that was in the festival, things that sounded rare and exotic and were, like Sankai Juku and Pina Bausch and all of these other wonderful, unpronounceable, mysterious names of artists, the question was asked, and is asked, was it an elitist festival only for the--the sort of cognoscenti, the people that were already in the know?

And my answer is no, it wasn't.

It was deliberately not a black-tie kind of festival for the Music Center crowd alone.

It's a festival that welcomed people.

Jenkins: They had gotten an invitation to be a part of the Olympic Arts Festival, and so they invited me to be a part of their project, so I was an artist in resident in their project.

Alonzo Davis: We commissioned 10 artists, including Judy Baca, Glenna Boltuch, Kent Twitchell, Richard Wyatt, myself, along with others, to do 10 murals on the freeway that led to and from, uh, the Coliseum, Harbor Freeway and the Hollywood Freeway.

Some of those murals still exist.

And it was a very successful, uh, adventure, and when we met with Mayor Bradley at the time, he said, "You guys are pretty bodacious."

Dale Davis: And we had these discussions along the lines of what it would mean to have all these different ethnic communities in L.A. being able to communicate with each other.

Alonzo Davis: By having formed a nonprofit, we were able to secure funding and support from various entities, including California Arts Council, City of Los Angeles, National Endowment for the Arts.

So we'd have that kind of range of participation from the political community, the entertainment community, as well as the business community.

And therefore, we could do events for free because we had the capital to make it happen.

And when that dried up, we dried up.

Ha ha ha ha!

Jackson: Alonzo and all the oth--some of the other artists who were in the CETA program were very much involved in the Olympics, but I wasn't in Los Angeles then.

I had left.

I was sort of fed up with Los Angeles, I think, but also, I was given the opportunity to go up to Idyllwild to teach at Idyllwild School of Music and the Arts, and during the summer program.

And then I loved it up there and I stayed, and I was there for a year.

Uh, I think Reagan became president, and I thought, "Oop, I'd better get a job," and it just turned out that the boarding school across the meadow actually needed a dance and fine arts instructor, and I was hired by them, and then they made me chair the department.

Jenkins: There was these guys from New York City who had come to--come to the boardwalk, and they had brought a Portapak.

This is the first time you have equipment that you could record and rewind, erase, and play and record over it again.

So...I started thinking about the whole notion of the way that the Watts Festival had been reported upon that was always about terror and, uh...horrible things would happen to you if you weren't African American.

Woman: I would like to say to the Spanish people that I'm very proud of this parade.

I'm very happy.

My name is Maria Davila.

I am from Lincoln Heights, from Nap.

We got here all color, all races.

This is beautiful.

This is the start of what can be really America.

Jenkins: So I went to the festival.

I got my friends to come with me, which became known as Video Venice News.

We record what was going on at the festival, which was totally not like what the media was actually reporting.

We were able to play the video that we had shot at--of the Watts festival on public access TV.

So that was the first time that we were able to record and to get the dis--some kind of distribution of what we had recorded, and when I started making video art, if I call it that, I was trying to be a critic of the images of Black people that were being made by mainstream media.

Dickson: We were just these little cubbyholes of individuals that at one point we were together.

The Park shows really brought us closer together, and when those started to break down, then we went further apart, going back--they went back to their institutions and studios, and so did I, so there was a breakdown there.

How do I successfully do what I do and survive and make money?

Public art ended up being that for me and doing public art projects like that.

I think that that's what happened.

I think we were sucked up by the world and trying to fulfill our identity as individual, creative people, and...that survival mechanism, because John needed to make money.

Noah got frustrated with the politics.

Greenfield: I was amazed that Alonzo was able to pull it off in so many--so many ways, and-- and some--somewhere deep down, I think maybe that was one of the reasons that the gallery closed, 'cause I think maybe Alonzo realized that he wanted to spend more time doing his work.

Alonzo Davis: It was, um...very difficult...to be the teacher, the artist, the gallerist, the husband--ha ha ha!--um, and have a life.

And then the art-making was in some ways my salvation, because it allowed me to explore and push my creative side, as opposed to the--all the other things that were sort of pulling and tugging at my identity.

Brockman Gallery is a launching pad.

My identity, for me, is as an artist, not as a gallerist, and because of that, I needed to separate gallery from Alonzo and make Alonzo the primary focus of my art practice and, uh, my personal direction.

This is the black-and-white image developed of a collage of multicultural images, and this is a, uh, color rendering, uh, of what we, uh, project to do.

Voice-over: I left L.A. and moved to Sacramento and, uh, became a director of a, uh, public art program, uh, for the city and county.

And, uh, that was my way of kind of reshuffling the cards.

Dale Davis: So I became a teacher.

I stepped into a program called APEX--Area Program for Enrichment Exchange--and it was getting students from other schools, other cultures to come to Dorsey High School.

Jenkins: I'd been having this conversation about these stories about L.A. art scene with lots of artists.

One who'd passed away, Jackie Apple, she gave me my first, actually, audio recordings of singing.

[Clears throat] And--and she just--she just passed away, Rudy Perez just passed away.

It's just like...I'm holding on, man.

Heh!

We're--all of us who get to a-- we get to a certain age, you know, and you see all your friends disappearing.

Tami Outterbridge: This is so important because it--it just shows the love, the relationship, um, between these two brothers and my father, that Alonzo would not only do the mural in the first place, in 1980, but that he would then, immediately after my father's passing, raise the funds to restore the mural.

And he said, "John Outterbridge may have passed, but he will never be forgotten.

And this is a way," he said, "of wrapping a soul."

And I will never forget that, so thank you for pulling this out.

Woman: That's beautiful.

Tami Outterbridge: Yeah.

[Distant music playing] [Man singing indistinctly] Tami Outterbridge: Here, each year, they honor a different set of ancestors.

And this year, my beautiful dad, John Outterbridge, is one of the ancestors being honored.

So we're so glad to be here.

And this is part of the arts community.

The creative community is here to support.

[Different music playing] [Man singing indistinctly] Keith: It's been absolutely amazing, you know, to see artists that I've either known for a long time, I have, um, admired for years and years.

To see the art world embracing artists like Suzanne Jackson or, like I said, John Outterbridge, who were so foundational to the L.A. art world that we know today, is really amazing.

They're still making work now.

You know, they're active, amazing artists, and so what I try and do is, just as much as I want to continue to celebrate their contributions that they continue to make, and they made in the sixties and seventies and eighties and beyond, they are still living and breathing artists.

Alison Saar: It's just really incredible to see how my mother has been embraced globally.

She just turned 98 and still in the studio every day; sometimes in her studio in the pajamas, but it's her studio.

She can wear whatever she wants to at the studio.

Kenturah Davis: I think the legacy of the Brockman Gallery is really about community, the fact that these artists who made such a range of work came together, talked about the work, challenged each other to really bring out the best in themselves and their peers.

That's huge, and the--and the fact that we now have this archive that documents so many artists who we now see as these kind of legends, not only among Black artists, but in the art world in general.

It's so important, and to now know that one of L.A.'s libraries is housing that archive and that there's a place to go and see it, that's just amazing.

Charles: This special collection is--it does not just hold artwork and photographs.

It actually houses documents and other ephemera that goes over the entire existence of the Brockman Gallery.

It represents people actively doing their part in uplifting a community and being a voice to the voiceless, providing representation to the youth.

It represents not just the present actions, but the forethought into the future community.

Keith: They didn't start this gallery with, you know, generational wealth or, you know, a huge amount of resources.

It was the conviction that they had that they believed that this gallery was needed and it could do well.

And every day, "We're just going to, like, show up and make this thing happen."

I hope that the legacy is just that--that the Brockman Gallery was and continues to be, you know, a dynamic hub for Black arts here in Los Angeles.

And I don't know where the conversation would be with--if we didn't have that gallery.

Simmons: I hope that this film can highlight to the broader world in the community how impactful these young brothers were in getting people to see the work by Black artists in a different way, as fine art, and how it was supporting Black art and artists, understanding the-- the production of the--the festivals and the concerts.

I mean, it was really that entrepreneurial spirit that was out of the mainstream.

Jackson: You have to be persistent, determined.

Practice, practice, practice.

Keep working.

You've got to show, be in group shows.

If I hadn't been in that show at the Watts Towers, I never would have met my friends, the artists.

We support one another; other artists will tell other people about you when you're in shows.

You get to be seen with them, but it's that coming from a place where you have a big imagination and you have ideas that you want to put down, and you just have to be persistent and keep trying and trying and trying.

Greenfield: Had it not been for Brockman Gallery and the people that I met through Brockman Gallery, I don't know if I would have been an artist.

I knew I had the--the ability to make the work, but I think the constant support and encouragement of some of the people that I met through Brockman are one of those things that gave me the strength to continue in the face of a lot of opposition.

And for that, I'll--I'll eternally be grateful.

Alonzo Davis: I always dreamed of being able to have the kind of time I have now.

I'm glad somewhere along the way, I saved some money so that, um, I could have a full studio and access to my creative spirit inside.

And as I tell other young people, it's like a long-distance race, and, uh, if you're not prepared to run the full marathon--heh!--you'll never cross the finish line.

Heh heh!

Dale Davis: Do something with your life that's meaningful, that's not classist, is not generation-based, is universal.

I think the key word, you know, it really is universality.

What is universal?

What can be learned by all and shared and given a life beyond whatever it is that you've done.

If that's a gift, give me that one.

[Music playing] Announcer: This program was made possible in part by a grant from Anne Ray Foundation, a Margaret A. Cargill Philanthropy; the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors through the Department of Arts & Culture, the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs, and the National Endowment for the Arts.

Black Art: A Brockman Gallery Legacy (Preview)

Preview: S15 Ep4 | 30s | Brockman Gallery was the center of a community of Black artists in L.A. from 1967-1990. (30s)

Dr. Joy Simmons' Collection Represents Decades of African American Art

Clip: S15 Ep4 | 1m 57s | One of the most important African American art collections lives in a Los Angeles home. (1m 57s)

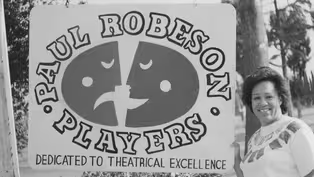

The Legacy of the Paul Robeson Players in 1970s L.A. Black Theater

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S15 Ep4 | 12m 4s | In 1970s Compton, the Paul Robeson Players emerge as one of L.A.'s longest-running Black theaters. (12m 4s)

'84 Olympic Freeway Mural Project Pulled Talent From Diverse L.A. Communities

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S15 Ep4 | 3m 56s | Ten murals in total were commissioned by artists of various ethnic backgrounds and styles. (3m 56s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Artbound is a local public television program presented by PBS SoCal