Inside the camp where Sudanese refugees have fled civil war

Clip: 4/15/2025 | 9m 57sVideo has Closed Captions

Inside the crowded camp where Sudanese refugees have fled violence and hunger

For two years now, Sudan has been wracked by a civil war between the Sudanese armed forces and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces. Correspondent Neha Wadekar and filmmaker Zoe Flood, with the support of the International Women’s Media Foundation, report on the crisis on Chad’s eastern border, where hundreds of thousands of Sudanese civilians have fled violence and the risk of starvation.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Major corporate funding for the PBS News Hour is provided by BDO, BNSF, Consumer Cellular, American Cruise Lines, and Raymond James. Funding for the PBS NewsHour Weekend is provided by...

Inside the camp where Sudanese refugees have fled civil war

Clip: 4/15/2025 | 9m 57sVideo has Closed Captions

For two years now, Sudan has been wracked by a civil war between the Sudanese armed forces and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces. Correspondent Neha Wadekar and filmmaker Zoe Flood, with the support of the International Women’s Media Foundation, report on the crisis on Chad’s eastern border, where hundreds of thousands of Sudanese civilians have fled violence and the risk of starvation.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch PBS News Hour

PBS News Hour is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipWILLIAM BRANGHAM: For two years now, Sudan has been torn apart by civil war as the Sudanese Armed Forces have fought with the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces.

Millions of Sudanese have fled, many to neighboring Chad.

The U.N. says it is now one of the worst humanitarian crises in recent memory, and caring for the millions in need has been made harder by the Trump administration's shutdown of USAID.

Correspondent Neha Wadekar and filmmaker Zoe Flood, with the support of the International Women's Media Foundation, traveled last year to document the crisis on Chad's eastern border, where hundreds of thousands fled violence, but then faced starvation.

They report now that the situation is, if anything, worse.

And a warning: Accounts and images in this story are disturbing.

ABDUSSALAM MOUSTAPHA, Displaced From Sudan: I come from Sudan, but now in Chad a refugee.

(through translator): In Sudan, we were always happy.

We played football with friends, but since we arrived here, we were not really happy.

NEHA WADEKAR: At 10 years old, Abdussalam Moustapha has already experienced more trauma than many adults ever will.

I met Abdussalam and his mother, Mounira, in a refugee camp on the Chad-Sudan border, where they live in the corner of a large tent partitioned among dozens of families.

MOUNIRA OUMAR MAHAMAT ABDALLAH, Displaced From Sudan (through translator): It was difficult to move around.

We set off to go to a nearby town that was safer.

We went late at night, but we were attacked on the road.

People were killed.

Some were hit by cars.

Everyone was running for their lives.

NEHA WADEKAR: Abdussalam and his family are among many thousands of non-Arab civilians who fled brutal attacks by the Arab Rapid Support Forces, or RSF, on West Darfur's capital city, Al-Junaynah.

The nonprofit Human Rights Watch described the waves of violence by the RSF and allied militias as a systematic campaign to remove, even by killing, members of the Masalit ethnic group.

ABDUSSALAM MOUSTAPHA (through translator): When I was coming back with my brother, we saw people killed on the road.

Some were slaughtered, some were beaten and tied up, and then, as we were walking, we were shot.

NEHA WADEKAR: Abdussalam's 5-year-old brother was shot dead while the boys were still holding hands.

Mounira found Abdussalam with a gunshot wound in his belly, his stomach covered with blood.

MOUNIRA OUMAR MAHAMAT ABDALLAH (through translator): My son could not walk, so I took him on my back.

In our family, more than 38 people were killed.

They raped women in front of us.

We were also beaten.

NEHA WADEKAR: Over 765,000 new Sudanese refugees have fled to Chad since fighting broke out in April 2023.

Already one of the poorest countries in the world, Chad is hosting one of the largest refugee populations of all of Sudan's neighbors.

Most escaped with almost nothing.

Many, like Bachir Sinin Barra, a used car dealer who also fled Al-Junaynah are deeply traumatized.

BACHIR SININ BARRA, Displaced From Sudan (through translator): I was walking, and then I was shot.

I fell down and I stayed there for days.

Now my arm is not working, nor is my leg.

And now, I can't walk.

NEHA WADEKAR: And it's a crisis that shows no sign of abating.

When we visited, an average 1,000 to 1, 500 people were crossing at the Adre border post every day.

Behind me is the border of Chad and Sudan, and over here is the line of new arrivals that are waiting to be screened.

We have been here all morning, and this line has stretched all the way back to the wall, even though they have been processing all morning.

We have been told that 72 percent of the new arrivals coming through this border point are children.

RAWDA YAYA IBRAHIM, Displaced From Sudan (through translator): My child is only 21 days old.

He was born after we had already fled our homes.

The Arabs attacked us and took our luggage.

Eight people were killed.

Some went missing.

NEHA WADEKAR: Many new arrivals end up in makeshift shelters at a transit camp outside the small border town of Adre, which used to have a population of just 40,000 people.

Today, Adre itself is hosting more than 235,000 refugees, as Ying Hu from the U.N.'s Refugee Agency told me.

YING HU, UNHCR: You can see the conditions are very dire.

There is no adequate basic services, such as water or health services, and they live in shelters that cannot withstand the weather.

So, what UNHCR is trying to do is to relocate them from the border area to safer locations.

NEHA WADEKAR: The U.N.'s Refugee Agency, UNHCR, can't work fast enough to build news sites with actual infrastructure.

Not only are more people arriving daily, but UNHCR's operations in Eastern Chad are chronically underfunded.

They have received just 17 percent of their $246 million appeal so far this year.

All aid agencies are stretched then across the globe, but humanitarians told me that it's especially bad here.

People leaving Sudan are fleeing not only war, but hunger as well.

Last year, famine was officially declared in a refugee camp in North Darfur.

Over 25 million people in Sudan faced acute hunger, and many refugees are arriving here already malnourished.

At this outpost in the Adre transit camp, health care workers assess children for malnutrition.

DONAIG LE DU, Chief of Communication, UNICEF Chad: This morning only, the team screened about 70 children, and one in four was actually severely acute malnourished.

And what does that mean to be severely acute malnourished?

It means their life is at stake, so they have to get treatment.

NEHA WADEKAR: The nonprofit Doctors Without Borders, known by its French acronym, MSF, has set up a pediatric malnutrition ward to treat serious cases.

SACHIN DESAI, Pediatrician, Doctors Without Borders: What we're entering here is our emergency or our kind of triage area.

And this actually will be expanding because we're in that period of the hunger season, as well as even kind of getting ready for a malaria season as well.

NEHA WADEKAR: Aziza Mahamat's 7-month-old baby had been ill for nearly a month when we met, since the family arrived in Chad.

He was hospitalized for severe malnutrition.

AZIZA SOUMAIN MAHAMAT, Displaced From Sudan (through translator): Since we arrived here, we haven't had enough food because we don't have any money.

I was given milk for the baby to drink.

I'm not happy about it.

I'm not happy.

NEHA WADEKAR: And while clinicians here are doing their best, MSF said that, when "News Hour" visited, between three to four children were dying of malnutrition and associated illnesses each week in this unit in Adre.

Meanwhile, aid agencies are already working around the clock to keep everyone fed.

This is a major food distribution site run by the World Food Program and its partners.

On average, they say between 15,000 and 20,000 people are served here per day.

These food distributions are supposed to happen monthly, but this one has been delayed due to funding constraints.

As you can see, people arrive here early and some of them have to wait all day in temperatures that are reaching above 110 degrees for their food rations.

WFP says that last year's lean season, which extended from June until August, was the worst in Chad's history so far.

The agency says it expects 2025 to be even worse, bringing a record number of people into food insecurity.

Maryam is looking after seven children on her own.

Her husband was killed in an attack in Darfur in late 2023.

MARYAM IBRAHIM SAIF ADDINE, Displaced From Sudan (through translator): I came here to wait for food early in the morning.

I didn't even take tea.

It's been almost four or five days since my children last ate any vegetables or meat.

NEHA WADEKAR: Added to the pervasive hunger, the specter of disease here in the overcrowded and often unsanitary temporary settlements.

ARISTIDE KENGNI, Doctors Without Borders: The main disease is for now because it's the dry season the respiratory tract infection, like flu, due to the dust and everything, and followed by diarrhea and malaria.

NEHA WADEKAR: Aid agencies are also racing to provide access to safe drinking water to avoid the spread of waterborne diseases in the camps.

Beyond the basics, the residents of these camps are doing all they can to rebuild their lives in what are seemingly impossible conditions.

Many children in the transit camp, where there is little formal infrastructure, have been out of school since the conflict started.

Some adults, such as these brothers who were lawyers back in Darfur, are taking the situation into their own hands, teaching children with whatever school materials they can get.

Older students are also finding ways to fill their time and reconnect with friends outside of the safety of the classrooms they left behind in Sudan.

But for too many young people, the trauma they have experienced means they're not able to return to normal life just yet.

ABDUSSALAM MOUSTAPHA (through translator): I can't play alone.

I don't have anybody to play with.

My friends say that, because I have had an operation, they cannot play with me.

NEHA WADEKAR: All of the young survivors of Sudan's violence have to try to heal, both in body and in mind.

Their parents can only hope that they will have the chance to feel young and free once again.

For "PBS News Hour," I'm Neha Wadekar in Adre, Chad.

China cuts exports of rare earth minerals amid trade war

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 4/15/2025 | 7m 37s | China cuts exports of vital rare earth minerals as trade war with U.S. intensifies (7m 37s)

Grants frozen as Harvard pushes back against Trump's demands

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 4/15/2025 | 6m 41s | Billions in grants frozen after Harvard pushes back against Trump's demands (6m 41s)

How college communities are reacting to funding threats

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 4/15/2025 | 5m 34s | How college communities are reacting to funding threats, international student arrests (5m 34s)

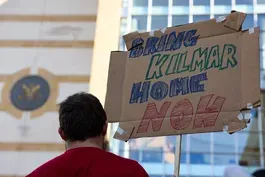

Judge presses DOJ on wrongfully deported man

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 4/15/2025 | 8m 54s | Judge presses Trump administration on why it hasn't returned wrongfully deported man (8m 54s)

News Wrap: Iran leader downplays chance of nuclear deal

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 4/15/2025 | 4m 58s | News Wrap: Iran's supreme leader downplays chance of deal from nuclear talks with U.S. (4m 58s)

Why abortions are rising in U.S. despite more restrictions

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 4/15/2025 | 7m 11s | Why abortions are rising in the U.S. despite more restrictions (7m 11s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Major corporate funding for the PBS News Hour is provided by BDO, BNSF, Consumer Cellular, American Cruise Lines, and Raymond James. Funding for the PBS NewsHour Weekend is provided by...