Washington Week full episode for Oct. 4, 2019

10/5/2019 | 25m 14sVideo has Closed Captions

Washington Week full episode for Oct. 4, 2019

Washington Week full episode for Oct. 4, 2019

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Major funding for “Washington Week with The Atlantic” is provided by Consumer Cellular, Otsuka, Kaiser Permanente, the Yuen Foundation, and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

Washington Week full episode for Oct. 4, 2019

10/5/2019 | 25m 14sVideo has Closed Captions

Washington Week full episode for Oct. 4, 2019

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Washington Week with The Atlantic

Washington Week with The Atlantic is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

10 big stories Washington Week covered

Washington Week came on the air February 23, 1967. In the 50 years that followed, we covered a lot of history-making events. Read up on 10 of the biggest stories Washington Week covered in its first 50 years.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipROBERT COSTA: President Trump's use of power ignites the impeachment debate.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: (From video.)

They've been trying to impeach me from the day I got elected.

ROBERT COSTA: President Trump remains defiant and unapologetic amid mounting scrutiny of his administration's pressuring of foreign leaders from Ukraine to China to investigate political rivals.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: (From video.)

China should start an investigation into the Bidens because what happened in China is just about as bad as what happened with Ukraine.

So I would say that President Zelensky - if it were me, I would recommend that they start an investigation into the Bidens.

ROBERT COSTA: He attacks the whistleblower and Congress.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: (From video.)

This country has to find out who that person was because that person's a spy, in my opinion.

ROBERT COSTA: House Democrats warn the White House it needs to provide answers and evidence.

REPRESENTATIVE ADAM SCHIFF (D-CA): (From video.)

The White House needs to understand that any action like that that forces us to litigate or have to consider litigation will be considered further evidence of obstruction of justice.

ROBERT COSTA: Next.

ANNOUNCER: This is Washington Week.

Once again, from Washington, moderator Robert Costa.

ROBERT COSTA: Good evening.

As President Trump openly encouraged foreign governments to investigate the Bidens this week, new evidence in the House impeachment probe - a batch of text messages released late Thursday night - revealed the Trump administration pressured Ukraine far beyond the president's July phone call with President Zelensky.

Peter Baker of The New York Times writes, "Envoys representing Mr. Trump sought to leverage the power of his office to prod Ukraine into opening investigations that would damage his Democratic opponents at home."

And Karoun Demirjian of The Washington Post reports that a top U.S. official texted "Are we now saying that security assistance and White House meetings are conditioned on investigations" and "I think it's crazy to withhold security assistance for help with a political campaign."

These text messages underscored that the president is facing mounting challenges not only about the whistleblower complaint, but about his use of power in American diplomacy.

Joining me tonight, Karoun Demirjian of The Washington Post, a congressional and national security reporter; Tim Alberta, chief political correspondent for POLITICO magazine; Susan Page, Washington bureau chief for USA Today; and Peter Baker, chief White House correspondent for The New York Times.

Peter, take us under the hood of what these text messages reveal about President Trump and how he's using his power on Ukraine.

PETER BAKER: Well, a couple things.

One, you get a picture of how much he had outsourced foreign policy in this area to Rudy Giuliani, right?

The people who are actually charged with leading our foreign policy in this area, the State Department and diplomats, were deferring, in effect, to this non-official - this lawyer for the president - in their dealings with Ukraine as he was trying to pressure them into these investigations.

The other thing you learn, I think, is that while the president has said repeatedly, including today, that there was no quid pro quo, there really was, at least in terms of a meeting at the White House, which the Ukraine president really, really wanted.

They made very clear that that meeting was not going to happen without a commitment to fight corruption - by corruption, of course, they meant Democratic investigations.

And then even one of the diplomats, Bill Taylor, who's based in Ukraine for the United States government, he repeated, as Karoun reported, his suspicion that the aid to Ukraine was also tied in a quid pro quo type of basis.

That was denied, but to him from his position in Kyiv that - it seemed clear to him that was what was going on.

ROBERT COSTA: We talked about your reporting, as well, on Capitol Hill all week, staking out the House Intelligence Committee.

Were these text messages the smoking gun for House Democrats?

KAROUN DEMIRJIAN: I think Democrats feel like this is the best piece of evidence they've gotten so far in trying to put together this - a narrative of what was going on here, surrounding what we first saw in the whistleblower's complaint, at the transcript of the July 25th call between the president - our president and the Ukrainian president, and now this rounds out even more of that story in terms of what the plans were leading up to that direct interaction and the cleanup afterwards, or the increased demands that were made afterwards of the Ukrainians if they wanted to actually be able to have that fully functional bilateral relationship between the heads of state.

Look, you're seeing just as much partisan division, though.

As excited as the Democrats are about having this document that makes their case, they believe, Republicans are pointing to the texts like the one that came from the U.S. ambassador to the EU, Gordon Sondland, who at the very, very end of this exchange says there was no quid pro quo here, I think we should take this off the text message chain and just talk on the telephone, and saying, look, that's proof that this was all in the legitimate course of business.

It's very striking to see how both parties are approaching this because the word "Biden" is never uttered in those text message chains; it's just the discussion about investigating the company for which Hunter Biden worked.

We know because of the president's public statements that that is basically code for looking at the Bidens in a politically motivated investigation, but it does not say that in the letter, and that's what gives Republicans room to say no quid pro quo here.

ROBERT COSTA: Tim, for Republicans, do these text messages cross the line?

When you talk to your sources privately, are they alarmed?

TIM ALBERTA: Privately, yes, and privately the have been alarmed by any number of things that the president has said and done for the last couple of years, Bob.

I don't think that that's new, and I don't expect there to be much of a break with the president publicly for the same reason that there has not been a break with the president publicly for the last couple of years in any number of these other instances, which is that these Republican elected officials in Washington, they're not hearing from their Republican constituents back in their districts about it.

They - ROBERT COSTA: They're hearing a little bit, perhaps.

TIM ALBERTA: Just a little bit, and it typically - you know, it's at the periphery.

If they hold a town hall, they'll have a couple of angry comments maybe from an independent voter here, a Democratic voter there, maybe even a disillusioned Republican once in a while.

But by and large when you talk to congressional Republicans, when you talk to their staff, they're getting almost nothing but overwhelming support for the president back in their red districts, so when they come back to Washington that's a message for them to hold the line, remain loyal to the president, at least publicly.

But yes, privately they continue to share with anybody who will listen that they are troubled, that they're deeply concerned, that if they had their way they might even be so bold as to break publicly with the president, but they know that it would probably be career suicide for them.

ROBERT COSTA: Susan, you're writing a biography of Speaker Pelosi.

What a fascinating figure at this moment in American history.

When she steps back and she looks at this new development of the text messages beyond just the whistleblower complaint, what's her calculus, what's her strategy?

SUSAN PAGE: Well, her calculus is that this is a new phase of the Trump presidency, this is different from where we've been before.

You know, contrast it with the Mueller report.

The Mueller investigation took two years, largely in secret, a confusing story, complicated.

We haven't hit the two-week mark yet on the Ukrainian story, but Republicans (sic; Democrats) now believe, including Speaker Pelosi I believe, that if they don't get one more document or one more piece of testimony they have the grounds to impeach President Trump, and I think it is all but inevitable that they will impeach him.

And the only question is, how big do they go?

Do they try to pursue these new strands that we see with pressuring China and Australia and Great Britain?

Can she control the Democratic caucus to not go into all the other things that some of them want to use to impeach President Trump?

But I think impeachment is not just on the table now; I think impeachment is now all but guaranteed.

ROBERT COSTA: Let's pick up on that point about maybe expanding this probe and this impeachment proceeding.

You were at the Capitol today, Karoun.

You saw the House Democrats are now asking Rudy Giuliani for documents, they're asking Secretary of State Pompeo, they're asking Vice President Pence.

Take us inside the House Intel Committee.

What's next?

What are you looking at?

KAROUN DEMIRJIAN: Well, I mean, it's the House Intel Committee and the House Foreign Affairs Committee and the House Oversight Committee, and it eventually has to go to Judiciary, right?

There is a potentially expanding pool here of people that you can tap.

Even if you just look at the whistleblower's complaint, which is what started this whole process off, it says that there is a dozen White House officials that were on that call and various other State Department and intel officials who were briefed on it.

That's a very broad pool, and if each of those people then names somebody else who puts together pieces of this puzzle - because remember, it's not just the one call; it's an entire spectrum of things that occurred before and after, too, that is giving people pause about what's going on here with the president's relationship with Ukraine and what he's trying to get out of the leadership.

So it's a very potentially exponential series of investigations that could go all the way further up the chain.

But what you've seen happen basically is that they are trying to make sure that they don't lose control of the time element by saying things like Adam Schiff said earlier this week, which was, well, we're going to consider if people do not comply with our very fast-moving demands for information and threats of subpoenas, then we're going to assume you have something to hide, and we're going to assume that makes our case for obstruction of justice, or contributes to it.

So this is not your traditional sphere of going back and forth with the White House.

It's moving at an incredibly quick clip.

ROBERT COSTA: Peter, we saw President Trump in the opening video of this program, defiant as ever.

What's your read on the president, not just as a reporter at the White House now but as a student of the presidency - defying Congress, having exchanges with reporters that are pretty contentious.

What's going on inside the West Wing?

PETER BAKER: Well, I think we saw him as riled up this week as we have seen him in the entire time of his presidency.

There have been other times, but this is about as agitated, I think, in public as he has been.

Clearly upset about this, clearly combative, clearly defensive, clearly miscalculated the impact releasing that rough transcript would have.

You know, if he honestly thought that that was going to exonerate him, it didn't have that impact, obviously.

There was no explicit quid pro quo in it.

He thought that was good enough.

But the implicit quid pro quo clearly energized Democrats and propelled them on this fast-paced impeachment.

Very different than past presidents.

Nixon, Clinton, both of them were emotionally distraught and consumed by their impeachment battles, but they didn't show it in public.

They tired, at least, not to show it in public.

They thought that was the key to survival.

President Trump doesn't hide anything.

He doesn't hold back.

(Laughter.)

If he's feeling it, we know it.

I think we saw a very honest - an honest portrayal of how he's feeling this week.

ROBERT COSTA: That was only one of the - SUSAN PAGE: You know, and so - and so isolated.

PETER BAKER: Yeah.

SUSAN PAGE: You know, that's another way, to contrast with the previous presidents we've seen at moments of crisis.

You know, there is not a person around him who is saying: Don't do that.

You can't do that.

Do this instead.

He is his own chief spokesman and chief strategist.

And that has served him well.

It got him elected to the presidency.

But that is a dangerous place to be at this moment.

ROBERT COSTA: Let's stay with that.

PETER BAKER: And even among Republicans - just back to Tim's point earlier - you're right, they're not condemning him.

I don't see them defending him, other than a handful of real hardcore - TIM ALBERTA: That's what feels slightly different about this particular episode.

PETER BAKER: Yeah.

They're in hiding.

They don't want to have anything to do with it if they can avoid it.

ROBERT COSTA: Let's talk about that for a second, because you have the entire Cabinet.

You mentioned no guardrails anymore, Susan.

But you have the secretary of state, Attorney General Bill Barr investigating the origins of the Russia investigation, Vice President Pence being called for documents.

We see Cabinet members this week being pulled into this wave.

Let's hear from a couple of them.

SECRETARY OF STATE MIKE POMPEO: (From video.)

As for was I on the phone call?

I was on the phone call.

VICE PRESIDENT MIKE PENCE: (From video.)

And he tasked me to go and meet with the president of Ukraine and carry our concerns about those issues.

And anyone that looks at the president's transcript will see that the president was raising issues that were appropriate, that were of genuine interest to the American people.

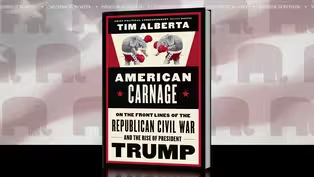

ROBERT COSTA: Tim, you wrote the bestselling book American Carnage about how the Republican Party became controlled by President Trump.

When you see these leaders in the Cabinet advocating for the president's position on foreign policy in Ukraine, what does it tell you?

TIM ALBERTA: Geez.

It tells us a lot of things, Bob.

I think first and foremost what it tells you is that everyone within the inner orbit, certainly, of the president, and even really within his outer orbit, they understand that if you are going to cross this president, if you are going to go to the mattresses with him, you're going to lose, right?

There is very little incentive for anyone in his inner circle, anybody in the West Wing, anybody in the administration of any authority or influence, to go toe to toe with him and to try and talk him down, much less to even just give him news that he doesn't want to hear, right, to try and dissuade him to try and sort of buffer him from his own worst instincts as, you know, Jim Mattis, and H.R.

McMaster, and Rex Tillerson and others tried so famously to do, and largely failed to do.

There is just no compelling reason for anyone - whether it's Rudy Giuliani, or Mick Mulvaney, or anybody else to tell the president that what he's doing is wrong, strategically or otherwise.

And the result of that is a president who feels as though, to your point a minute ago, Bob, there are no guardrails.

There is no - there is no envelope to push here.

He is just sort of on his own.

And nobody seems to be telling him that he can't do what he's doing.

ROBERT COSTA: But we did see Kurt Volker this week, the envoy to Ukraine who's now left.

He did tell Rudy Giuliani that some of these conspiracy theories about corruption in Ukraine or different views were not credible.

KAROUN DEMIRJIAN: Right.

I mean, you saw in those text messages how Kurt Volker was kind of caught in the middle of both trying to mitigate what Giuliani was doing and saying, and dissuade him, but when that failed being the go-between because he wanted to preserve some sort of relationship between Trump and the Ukrainian president, because the alternative is that, you know, you disadvantage Ukraine vis-a-vis Russia because there's an actual war and occupation going on over there.

But, you know, Volker's not in elected office.

He is a former McCain guy.

And he kind of is in that school of thought about how foreign policy should be done.

And when he was called to testify before - or, be deposed before these House committees, he resigned his post as special envoy.

There's not that many Volkers in there, and there's not that many Volkers that are sitting in Congress right now.

So the question is, you know, as Tim was putting out, they've kind of become used to this process of seeing the president just do, and do, and do and say: Tell me it's wrong.

You're not telling me it's wrong.

It would have to be - I don't know where exactly the line is, because so many members of Congress has been defending so much, where they might break in this process.

You've seen people like Mitt Romney do it, but you haven't seen that many more people join that chorus.

SUSAN PAGE: But, you know, I don't think the president probably loses support among Republican members of Congress until he loses support among Republican voters across the country.

And one of the things we found in a new USA Today/Ipsos poll we did this week was that the president still has the support of Republicans.

Republicans oppose impeaching the president.

But there were a couple red flags, I thought, for the president in the findings.

One is that 30 percent of Republicans said it was an abuse of power for a president to pressure the president of another country to help him investigate a political rival - 30 percent.

That's not nothing.

Eighty percent of Republicans said the president is not above the law.

That is a higher number than for either Democrats or independents.

ROBERT COSTA: Looking at that data, Peter, why does Vice President Pence, we saw the video, remain in such lockstep with President Trump?

Same with Secretary of State Pompeo.

What is their positioning?

PETER BAKER: Well, I think it's partly what Tim talked about.

Republicans at this point have learned that crossing the president doesn't pay.

It didn't pay for Rex Tillerson, or Jim Mattis, or any of these others who tried to restrain him.

And so the current crop, the current people around him, are not in fact the, you know, committee to save America that the first generation of aides were.

(Laughter.)

These are the people who've decided to be there to help him, and enable him, and perhaps steer him, if they can.

But Mick Mulvaney is the chief of staff.

He is in his tenth month as acting chief of staff.

He doesn't even have the full title.

It doesn't require Senate confirmation.

Has nothing to do with that.

It's just the president doesn't want to give him the full title.

That is emasculating for anybody, as it makes it very hard for anybody to do your job if you don't even have the full title behind you.

TIM ALBERTA: You know, I'm reminded of a conversation I had with Paul Ryan, the former House speaker, just after he'd retired.

This is maybe three weeks after he had left office.

And he was describing to me how in the first year he was president that Donald Trump really seemed to respond to a Jim Mattis, or a Rex Tillerson, or a H.R.

McMaster, or even a Reince Priebus once in a while, who would push back on him, who would attempt to say, Mr. President, here's the line.

Here's how far up you - how close you can get to that line.

But you can't go over it.

And Ryan described to me this sort of gradual evolution where sort of month by month on the job the president began to become more comfortable with pushing up next to that line, and then crossing it.

And then when he would realize there was really no consequence for crossing it, he would continue to cross it.

And eventually he got to a point where he just stopped listening altogether.

And when you get to that point, I think that's where we are now.

And we're probably even well beyond it.

ROBERT COSTA: And it's not just he's not listening to Cabinet members.

He's listening to new people outside, like Rudy Giuliani.

The ascent of Giuliani is part of this story.

KAROUN DEMIRJIAN: It definitely is.

And Giuliani also kind of has this devil-may-care attitude, where he's leaned into what he believes is what he thinks is advantageous and politically correct.

And so - and isn't really letting anybody stop him.

He also goes out on television and makes statements that seem to advance the case against the president, except that it isn't really changing where the pendulum is swinging in terms of where the political line is between who supports and who criticizes the president.

And at the end of the day, I know that you were quoting the statistics that the president is not above the law, and 80 percent of the Republican Party thinks that.

This is not going to be decided in a court of law.

We are talking about legal procedures.

We are talking about legal arguments.

But we're also talking about squishing it all into just a few months.

This is a political process, fundamentally.

And the arguments that both sides are making at the end of the day are going to depend on that.

ROBERT COSTA: So while these investigations consume Washington, members of Congress are attempting to shine the spotlight on other issues ahead of the 2020 election.

Here is what House Speaker Pelosi said at her weekly news conference.

QUESTIONER: (From video.)

Do you have plans, or have you taken off the table the idea of a full House vote on an impeachment inquiry?

HOUSE SPEAKER NANCY PELOSI (D-CA): (From video.)

I'm first doing H.R.3.

Anyone on H.R.3?

Does anybody in this room care about the cost of prescription drugs and what it means to America's working families?

Does anyone care about the USMCA - U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement?

ROBERT COSTA: Meanwhile, Republicans are trying to talk up the USMCA trade deal but are facing tough questions from some constituents during this fall recess.

Here is Senator Joni Ernst of Iowa this week, when asked about President Trump.

SENATOR JONI ERNST (R-IA): (From video.)

I can't speak for him.

I'll just say that I can't speak for him.

QUESTIONER: (From video.)

I know you can't speak for him, but you can speak for yourself.

ROBERT COSTA: She can't speak for President Trump.

But when you saw Speaker Pelosi talking about USMCA and drug pricing this week, is that because she knows suburban voters who gave her the House majority in 2018, among others, want to talk about things beyond impeachment?

SUSAN PAGE: So she was up, I was there, it was her weekly news conference.

It had, like, triple the number of reporters she usually draws for a weekly news conference and every reporter there wanted to ask about impeachment, and she refused to take questions on impeachment until she had entertained questions on other topics because, exactly right, she knows that when it comes to voting next year voters are going to care more about themselves than they are going to care about President - what's happened to President Trump.

And you reach what voters care about, can they afford their prescription drug prices and other issues like that.

KAROUN DEMIRJIAN: Right, that's Democrats' challenge, to be able to both be very, very focused on impeachment for the next few weeks and months, and then try to translate that on the campaign trail and not be compromised.

But I also just - it was interesting that you played that Joni Ernst clip right there.

I mean, that was a very polite exchange.

It reminds me a lot of what the day-to-day reporting is like in the Capitol, trying to get Republicans to comment on what they think the president has said.

This is classic what they do: he doesn't speak for me, I'm not going to comment; sometimes it's I didn't hear what he said.

It's deflect, deflect, deflect, and that does not seem to be changing.

That seems to be the modus operandi.

We'll see if it continues to work.

ROBERT COSTA: Senator Ernst is up in 2020 for her reelection.

Others, like Senator Susan Collins of Maine, Senator Cory Gardner of Colorado, could the 2020 Republicans who are running for reelection plus the retiring Republicans, are those the Republicans most likely to possibly break?

TIM ALBERTA: I think it depends, Bob.

Again, what we saw there with Joni Ernst is interesting, and we - that's maybe one tiny drip in the pan.

We'd need to see a lot more drip, drip, drip back in these states.

Look, if you're Cory Gardner and you want to survive in Colorado in 2020, you're going to need ticket splitters because President Trump is probably not going to carry Colorado, right?

Joni Ernst, on the other hand, she's in a little bit of a different position.

You know, President Trump carried Iowa by a bigger margin than he carried Texas by in 2016, so she may not need the ticket splitters.

If she just stays loyal and rides the coattails, then she could be in decent shape.

So it's going to be a case-by-case basis, I think, for a lot of those senators.

ROBERT COSTA: How much does the state of the economy matter as we look ahead to 2020?

PETER BAKER: That's a great question because today we got the numbers, the latest numbers: 3.5 percent unemployment, another tick down; I think 130,000 new jobs.

As long as the economy is doing well, that, obviously, bolsters the president.

That's one of the things that kept President Clinton doing well in 1998, when he faced impeachment.

If the economy were in fact to go south - and there's been rumblings and concerns about that - that might be the kind of thing that begins to change those poll numbers among Republicans, not just Democrats and independents, and if that happens perhaps Republican lawmakers follow suit.

But as long as the economy is doing well, a lot of people say, hey, I don't care about the circus, I got a good job.

ROBERT COSTA: You wrote the book - you co-wrote the book Impeachment about the whole process.

What's different now about impeachment versus 1998 and 1973-74?

PETER BAKER: So many things, and yet some things are also parallel, right?

You know, back in 1998 you heard Democrats say this is a coup against an elected president, this is illegitimate, and the Republicans were saying we're for the rule of law and everything, and now you see the exact opposite.

Everybody, you know, where you stand depends on where you sit, obviously.

People like Nancy Pelosi were there, Jerry Nadler, you know, Chuck Schumer, some of these same characters, Lindsey Graham, making the exact opposite arguments today than they made back then.

But broadly, of course, the subject matter is so much different, right?

That was about lying under oath and obstruction of justice, which were serious; but it was about sex, which seemed less serious, right?

This is about the abuse of power in our foreign relations and it's a - it's a more weighty moment, and yet the country is even more polarized than it was back then.

I think back then we thought it was polarized; we didn't realize how polarized it could get.

SUSAN PAGE: You know, I didn't cover Watergate but I covered the Clinton impeachment, as did - as did you, and this has just so much a stronger feeling of peril - of peril for the country on all sides.

I think Americans just feel this is - there's something more fundamental at stake, either defenders of the president feeling like it's an effort to overturn the results of an election, Democrats - opponents of the president feeling like he's attacked fundamental institutions.

So it's just a - it's different in tone and in, I don't know, gravity.

KAROUN DEMIRJIAN: Also, it also cuts to one of the most existential foreign policy questions that we've been facing for like the last century, right?

We're talking about a great-power competition even if we're talking about Ukraine right now.

Ukraine, for - I used to be based in Moscow; I've covered this part of the world - it's often about Ukraine when you're talking about Russia, and here we are again in that situation where it's about the smaller person that's caught in the middle of this struggle.

And that is, you know, kind of the side story to the election interference story that we were all discussing in the nitty gritty of whether this was right or wrong what President Trump was doing, but there are those greater implications as well, and that's world-shifting, potentially.

TIM ALBERTA: You know, there's a real sweeping irony when you get to the nuts and bolts of the impeachment process and who's at center stage.

You mentioned, Bob, that Democrats won back the House in 2018 on the strength of taking back dozens of suburban-anchored, two-car-garage, college-educated, affluent suburban districts, and now some of those Democrats who flipped those formerly red districts who said they wanted to come to Washington and do anything but engage in a partisan exercise, now they're in the middle of a partisan exercise and it's probably going to define their careers.

ROBERT COSTA: We're going to have to leave it there.

Tim, welcome to Washington Week; so glad to have you at the table and glad to have everyone here, as always, on a Friday night, and thank you for joining us.

The Washington Week Extra is coming up next.

We will discuss Tim's book, the bestseller American Carnage.

You can catch that on our website, Facebook, or YouTube.

I'm Robert Costa.

Have a great weekend.

Washington Week Extra for Oct. 4, 2019

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 10/5/2019 | 10m 28s | Washington Week Extra for Oct. 4, 2019 (10m 28s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Major funding for “Washington Week with The Atlantic” is provided by Consumer Cellular, Otsuka, Kaiser Permanente, the Yuen Foundation, and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.